Solidarity Forever

Why I Wrote Solidarity Forever

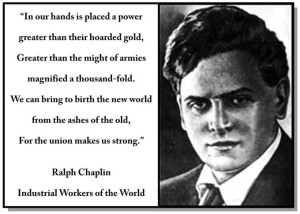

By Ralph Chaplin – American West, 1968; Introduction by Bruce Le Roy

Host: Doug “GoatHollow” on They Were Preppers

In the pantheon of American labor history there is a very special place for Ralph Chaplin, the man and his work. As the poet laureate of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), he is probably remembered best for giving organized labor its fighting them song, Solidarity Forever. But to those of us who were privileged to work with him at the Washington State Historical Society during the last few years of his life, Ralph Chaplin will always be honored for more, much more.

In the pantheon of American labor history there is a very special place for Ralph Chaplin, the man and his work. As the poet laureate of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), he is probably remembered best for giving organized labor its fighting them song, Solidarity Forever. But to those of us who were privileged to work with him at the Washington State Historical Society during the last few years of his life, Ralph Chaplin will always be honored for more, much more.

His love affair with the Pacific Northwest was revealed time and again in his writings as well as in his conversation. This rugged region of mountains and Puget Sound, of epic pioneering and great conflicts provided a satisfying backdrop for the unfolding drama of labor history. The “Free Speech” fights at Spokane, Everett, Tacoma, and other cities on the Northwest Coast were milestones to Ralph Chaplin. He reported that crises that exploded into gunfire and tragedy at Everett and Centralia. In the 1960 essay that follows this introduction, Chaplin writes: “Even at this late hour I am more grimly convinced than ever that neither the song itself nor the organization that sparked it could have emerged from any environment other than the Pacific Northwest in the afterglow of the rugged period of American pioneering”.

Further on, he says: “It is true that Solidarity Forever was written in Chicago, but it is also true that nobody ever heard of it until fifty thousand striking Puget Sound loggers bellered it out to a world that didn’t care a hoot about the problems of voteless and cruelly exploited ‘timber beasts’.”

Further on, he says: “It is true that Solidarity Forever was written in Chicago, but it is also true that nobody ever heard of it until fifty thousand striking Puget Sound loggers bellered it out to a world that didn’t care a hoot about the problems of voteless and cruelly exploited ‘timber beasts’.”

In his autobiography, Wobbly: The Rough and Tumble Story of an American Radical, Chaplin tells how he began the writing of “Solidarity Forever” during the Kanawha miners’ strike in Huntington, West Virginia. The song was not finished until January 17, 1915 in Chicago, on the day of a giant “Hunger Demonstration”. The twenty-eight-year-old author already had an intimate knowledge of labor conflict, beginning with his father’s account of the Haymarket Square Riot in the strife-torn Chicago of 1886, and proceeding through Ralph’s personal involvement with strikes in Chicago and West Virginia.

Wobbly is the sensitive and honest account of the evolution of an artistic youth into a rugged and effective labor editor, who survived riots, beatings, and imprisonment for his political beliefs. As the right-hand man of Big Bill Haywood, the crusading (General Secretary-Treasurer) of the IWW, Chaplin was generally where the action was. However, much was deleted from the first draft of Wobbly, as the original manuscript in the Washington State Historical Society shows. The author told me that the editors of the press that published Wobbly also cut many passages from the book.

Wobbly is the sensitive and honest account of the evolution of an artistic youth into a rugged and effective labor editor, who survived riots, beatings, and imprisonment for his political beliefs. As the right-hand man of Big Bill Haywood, the crusading (General Secretary-Treasurer) of the IWW, Chaplin was generally where the action was. However, much was deleted from the first draft of Wobbly, as the original manuscript in the Washington State Historical Society shows. The author told me that the editors of the press that published Wobbly also cut many passages from the book.

By the time Ralph Chaplin joined the staff of the Washington State Historical Society, more than a decade had elapsed since the publication of his autobiography. After he had been there nearly two years, I asked him why he did write a kind of “addendum” to Wobbly, giving some of his ideas about the great changes that had taken place in the American labor movement since he joined it as a youth. He was hard to convince, arguing that the book told most of the story. But finally he succumbed to the idea that he owed it to posterity to make some final statement.

With one major exception, “Why I Wrote ‘Solidarity Forever’” is the last important bit of writing that Ralph completed before his death in 1961. That exception is his epic poem, Only the Drums Remembered: A Memento for Leschi, which is the distillation of a lengthy sympathetic study of the dispossessed Indian. The protagonist of the poem is a chief of the Nisqually tribe of western Washington. History has pretty well proven that Leschi executed on a trumped-up charge of murder, served as a scapegoat for the Indian War of 1855. Chaplin felt a strange almost mystical identification with the great Indian leader. What his poem was to Chaplin the poet, “Why I Wrote ‘Solidarity Forever’” was to Chaplin the labor historian.

He predicted that the article “would cause equal consternation to the godly and the ungodly” . (Characteristically, he immediately credited the remark to William Lyon Phelps, who made it upon the occasion of his appointment as Literary Editor for Esquire magazine). Vigorously independent in his judgments, Ralph would not have been overly concerned with whatever consternation the essay might inspire. The years of physical and literary combat with one Establishment or another had toughened him against reaction. He speaks here with a voice of another age – an age in which a man was often held to account for what he said in no uncertain terms. In spite of the sharp vigor of his opinions, however, it would be a mistake to assume that Chaplin is simply calling down a plague on both labor and management in the present age. To accept that interpretation would do injustice to a truly complex mind. Ralph saw in the evolution of the labor movement a deplorable distortion of its beginnings, yet he never abandoned hope in the same “grass roots unionism” that had marked his era. But let him speak for himself in this first publication of his only supplement to Wobbly, a book now accepted as a classic of American labor history.

–Bruce Le Roy.

Follow GoatHollows youtube https://www.youtube.com/user/GoatHollow

GoatHollow Blog, News links and more http://preppingwithgoathollow.blogspot.com/

Listen to this broadcast of Solidarity Forever in player below!

You can also listen to archived shows of all our hosts . Go to show schedule tab at top of page!

Put our players on your web site Go Here!

You can also listen, download, or use your own default player for this show by clicking Here!

labor history Ralph Chaplin Solidarity Solidarity Forever They Were Preppers