Along the Suffrage Trail` From West to East for FREEDOM NOW!

Along the Suffrage Trail` From West to East for FREEDOM NOW!

By: Amelia Fry

Part of preparedness for most of us has not only been the effort put forth to protect ourselves from unforeseeable events but to also protect ourselves from tyranny, the loss of freedom and liberty. The following article describes a major campaign won by strong Women, strong enough and with enough determination to take on government at all levels… and win. A reminder that change can be made with courage and determination. Gman

The place was San Francisco. The time was September 16, 1915, and in the brilliant lights of the Panama Pacific International Exposition the first Women Voters’ Convention was staging its grand finale – a spectacular send-off of petite Sara Bard Field and her fellow envoy, Frances Jolliffe, on one more woman suffrage campaign. What made this campaign different was that it was to be entirely by auto, entirely across the continent, and entirely by women. The mission: to symbolize the offer of the political power of the enfranchised women of the West to their voteless sisters in the East. The plan was direct and dramatic – direct because they would take a suffrage petition to President Woodrow Wilson and to the Congress for the opening day of its 1915 – 1916 session; dramatic because in all major cities along the route they would stage parades and rallies, garner public statements of support from congressmen in their home territories, and add thousands of names to the petition – which already had half a million signatures on a roll of paper 18,333 feet long.

The place was San Francisco. The time was September 16, 1915, and in the brilliant lights of the Panama Pacific International Exposition the first Women Voters’ Convention was staging its grand finale – a spectacular send-off of petite Sara Bard Field and her fellow envoy, Frances Jolliffe, on one more woman suffrage campaign. What made this campaign different was that it was to be entirely by auto, entirely across the continent, and entirely by women. The mission: to symbolize the offer of the political power of the enfranchised women of the West to their voteless sisters in the East. The plan was direct and dramatic – direct because they would take a suffrage petition to President Woodrow Wilson and to the Congress for the opening day of its 1915 – 1916 session; dramatic because in all major cities along the route they would stage parades and rallies, garner public statements of support from congressmen in their home territories, and add thousands of names to the petition – which already had half a million signatures on a roll of paper 18,333 feet long.

The trip was a fitting climax to the five-day convention that had been launched by more than a thousand determined women on September 11. These women were a new breed of suffragist – most of them young, well-educated, socially poised. Militant and aggressive, they looked back impatiently to the long years of piece-meal campaigns in individual states, campaigns effective only in the enlightened West. After fifty years of political combat, only twelve states – all of them western – had granted suffrage to women. For the woman gathered in San Francisco, this was not enough. They wanted freedom now and wanted it on a national level.

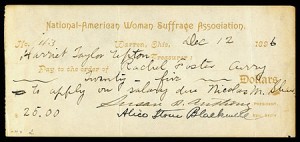

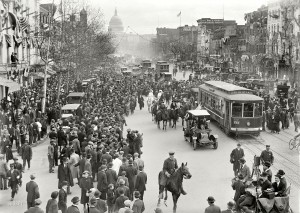

Their activist tactics had already caused them to split from the more sedate parent organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The child of this dissent, the congressional Union, was something of a press agent’s dream; flamboyant, dramatic, and single-purposed, it specialized in parades, demonstrations, pageantry, and the utilization of dignified affairs of state for its own ends – as when its members had held aloft their suffrage banners in the Capitol rotunda during the formal opening of the last Congress, or when, thousands strong, they had marched in stately procession down Pennsylvania Avenue during President Wilson’s inauguration. (This latter demonstration had incited crowds to riot, forced federal troops out, inspired the Senate to investigate, and caused the dismissal of the chief of police.)

Their activist tactics had already caused them to split from the more sedate parent organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The child of this dissent, the congressional Union, was something of a press agent’s dream; flamboyant, dramatic, and single-purposed, it specialized in parades, demonstrations, pageantry, and the utilization of dignified affairs of state for its own ends – as when its members had held aloft their suffrage banners in the Capitol rotunda during the formal opening of the last Congress, or when, thousands strong, they had marched in stately procession down Pennsylvania Avenue during President Wilson’s inauguration. (This latter demonstration had incited crowds to riot, forced federal troops out, inspired the Senate to investigate, and caused the dismissal of the chief of police.)

The battle cry of the San Francisco convention was “United”, for only the united woman-power of four million western votes could force a federal constitutional amendment through Congress, thereby bringing the franchise to the twenty million voteless women of America. At the convention’s opening luncheon, the movement’s major angel, Mrs. O.H.P. Belmont of New York, fired the determination of the thousands of women guest with a speech ghost-written for her by Sara Bard Field: “The women voters of the twelve enfranchised states… are met here to form a body politic … The western woman, with the power of her ballot, will give to her enslaved sister justice and freedom.

“What greater privilege can be ours, or land send forth a more blessed message!” The message was the Susan B. Anthony amendment: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” All summer long the words had hung emblazoned across the wall of the Congressional Union’s booth in the fair’s Educational Pavilion. Visitors had strolled by, red it, and added their names to the suffragist petition.

The organizing genius behind the Union’s activities at the fair – including the booth, the convention and the culminating automobile campaign – was its president, Alice Paul, a quiet, blue-eyed wisp of a woman fresh from the Pankhurst campaigns in England. Today in her late seventies, still vigorous and forthright as head of the Woman’s Party, Miss Paul recently recalled in Washington her reasons for the automobile campaign: “Why not?” Two Swedish women volunteered their car. They had just bought it, said they were going to drive it back to Rhode Island. We had already gone into many places campaigning with an auto. It was the easiest and least expensive way to have a campaign: drive into a town, speak on the car at street corners. We were there in San Francisco and we had to get the petition to Washington. The weather was still good. Sara was out there, free to go, willing, and lovely. A very good speaker. She was just sent to us from heaven.”

The organizing genius behind the Union’s activities at the fair – including the booth, the convention and the culminating automobile campaign – was its president, Alice Paul, a quiet, blue-eyed wisp of a woman fresh from the Pankhurst campaigns in England. Today in her late seventies, still vigorous and forthright as head of the Woman’s Party, Miss Paul recently recalled in Washington her reasons for the automobile campaign: “Why not?” Two Swedish women volunteered their car. They had just bought it, said they were going to drive it back to Rhode Island. We had already gone into many places campaigning with an auto. It was the easiest and least expensive way to have a campaign: drive into a town, speak on the car at street corners. We were there in San Francisco and we had to get the petition to Washington. The weather was still good. Sara was out there, free to go, willing, and lovely. A very good speaker. She was just sent to us from heaven.”

Sara herself recalls that she was at first a most reluctant angel: “Alice came to me and announced that they had found these women and that they would drive me across the continent.

“’But Alice.’ I said, ‘do you realize that service stations across the country are very scarce, and you have to have a great deal of mechanical knowledge in case the car has something break down?”

“ ‘ Oh well,’ she said ‘if that happens, I’m sure some good man will come along to help you,”

Sara’s reluctance was understandable enough. The state of the nation’s highways in 1915 was not likely to inspire confidence, and the much-touted Lincoln Highway across the continent was in many places little more than a wagon track. The very week she was to leave, a local newspaper headlined a trip made by a woman from Denver to San Francisco: “We drove a hundred miles out of the way,” the woman told a reporter, “and got into roads where the middle was so high that the front wheels did not touch the road at all. … We forded streams where the water came up to the hubs … We went through sand that came almost up to the running-boards.” Travel time was no small consideration. The American Automobile Association had recently sponsored a cross-country endurance drive that set a new transcontinental speed record – 19 days, 18 hours, and 15 minutes – with 505 miles of detour. Altogether, the young suffragist could be forgiven her uncertain fortitude. But the gentle persuasion and persistence of Alice Paul could not be denied, and Sara ultimately gave in to the idea.

With only days to prepare for the journey, Sara hastily arranged for her two children to stay with their father, her “divorced Baptist-minister husband, in Berkeley. She shopped for a fashionable brown travel suit with a warm fur collar at San Francisco’s White House and notified her fiancé lawyer-poet Charles Erskine Scott Wood, in Portland, of her plans. Wood rushed down for the grand send-off and presented Sara with a heavy robe of buffalo fur – which would come in handy. With the “Great Demand” banner packed, and Frances Jolliffe, her traveling companion, beside her, the young suffragist was ready. No one thought to put in a map.

“As the car rolled through the great gates,: Sara remembers, “I was pretty shaken by it all inside. And those Swedes – the driver and the “mechanician’ – were strange ones, rather grim-looking. Also I knew Frances Jolliffe was going to cave in at the last moment. I just felt that would happen.”

“As the car rolled through the great gates,: Sara remembers, “I was pretty shaken by it all inside. And those Swedes – the driver and the “mechanician’ – were strange ones, rather grim-looking. Also I knew Frances Jolliffe was going to cave in at the last moment. I just felt that would happen.”

Sara was right. By the time the car reached Sacramento and was prepared for the trip over the Sierras to Reno, Frances had fallen ill and left the party.

An invisible – and perhaps more crucial – envoy remained, however, Mabel Vernon, advance press agent, parade organizer, and chief of arrangements, traveled ahead to each city by train and rounded up auto cades, bands, mayors, congressmen, and governors for Sara’s receptions.

In Reno, as in Sacramento, new chapters of the Congressional Union materialized out of Sara’s overnight stay. Names were added to the petition, often during impromptu street corner speeches from the top of the little car. In Sacramento, Congressman Charles F. Curry declared himself in favor of the amendment, and in Reno, Anne Martin, who had led the suffrage campaign to victory in Nevada the year before, joined Sara as a speaker at the suffrage meetings and the street-corner rump sessions. Sara reported to the C.U. headquarters in Washington that “the press is interested in our trip and ‘eats up’ the news we have to offer.”

Reno was the jumping-off place for the Great American Desert and marked the apparent evaporation of the Lincoln Highway – a navigational trap that the maples trio of women was ill-equipped to avoid. They found their way to the little towns of Fallon and Lovelock, where they could not resist a car-top speech or two but somewhere out of Winnemucca they followed the wrong trail, and became wanderers in a six-hundred mile wasteland. Salt Lake City – where Mabel Vernon was already organizing women and dignitaries – might as well have been in Tanganyika.

Sara still speaks of that night of endless wandering. Even with her buffalo robe, “the bitter cold of the night and the utter desolation of the whole country and the fear that we would not have enough gasoline to get to a filling station kept us agitated and in a good deal of physical distress.” Not until the half-light of a desert sunrise did they spot some low buildings that Sara remembers as the Ibapaw Ranch, where the travelers were restored with hot coffee, a huge fire in the kitchen stove, a ranchhand breakfast, and – best of all – a map.

Miraculously, they made Salt Lake City on time. Mable Vernon had done her job well: a local reporter wrote that ten automobiles, “loaded with more than a score of Salt Lake’s most prominent women,” met the dusty Overland. The parade rolled triumphantly to the steps of the state capitol where Governor William spry, Mayor Samuel C. Park, and Congressman Jo Howell waited for Sara. That night the poet-envoy wrote to headquarters: “While the earth was glowing in the light of the flaming sunset, and the mountains about stood like everlasting witnesses, Representative joseph Howell pledged his full and unqualified support.”

Miraculously, they made Salt Lake City on time. Mable Vernon had done her job well: a local reporter wrote that ten automobiles, “loaded with more than a score of Salt Lake’s most prominent women,” met the dusty Overland. The parade rolled triumphantly to the steps of the state capitol where Governor William spry, Mayor Samuel C. Park, and Congressman Jo Howell waited for Sara. That night the poet-envoy wrote to headquarters: “While the earth was glowing in the light of the flaming sunset, and the mountains about stood like everlasting witnesses, Representative joseph Howell pledged his full and unqualified support.”

As the car turned toward Wyoming Miss Kindstedt began complaining about the unaccustomed servitude of her role as :mechanician,” jealous of Sara who made all the speeches and stood in the spotlight. The Swede’s unfortunate English made oratory a preposterous notion, but at the same time made it difficult for Sara to soother her with kinds words. It was perhaps just as well that Sara did not learn until after the trip that Miss Kindstedt had only recently been released from a mental hospital. That some investigation should have been made of the two women occurred to Sara and Alice Paul only in hindsight. “They were willing to take me along for nothing, and that was good enough.” Sara recalls.

As they entered Wyoming and the inevitable snow, blizzards and high drifts hardly impeded their progress. While Sara huddled in the buffalo robe and horrified male motorists shouted warnings as they passed, the Swedes “piled right on, never knowing where we might be held up by impassable snow. Every now and then we would get out and stomp our feet and keep circulation in motion.” Exercise was further encouraged by the man-sized drifts that required all three to get out and push. In Cheyenne the mayor, governor Kendrick, and Senator Warren lengthened the petition with their names, and another CU chapter bloomed in the wake of the envoy. In Denver , the Overland – bedecked as always in banners and the “Great Demand” flag – was escorted to the governor by a band and twenty autos similarly arrayed.l The local congressman promised his support. The next day Colorado Springs women, inspired and abetted by Mabel Vernon, made news with their grand extravaganza – a women’s chorale, complete with purple and gold gowns, suffrage songs, marches and speeches.

As they entered Wyoming and the inevitable snow, blizzards and high drifts hardly impeded their progress. While Sara huddled in the buffalo robe and horrified male motorists shouted warnings as they passed, the Swedes “piled right on, never knowing where we might be held up by impassable snow. Every now and then we would get out and stomp our feet and keep circulation in motion.” Exercise was further encouraged by the man-sized drifts that required all three to get out and push. In Cheyenne the mayor, governor Kendrick, and Senator Warren lengthened the petition with their names, and another CU chapter bloomed in the wake of the envoy. In Denver , the Overland – bedecked as always in banners and the “Great Demand” flag – was escorted to the governor by a band and twenty autos similarly arrayed.l The local congressman promised his support. The next day Colorado Springs women, inspired and abetted by Mabel Vernon, made news with their grand extravaganza – a women’s chorale, complete with purple and gold gowns, suffrage songs, marches and speeches.

The trip south across the plans of Kansas might have quieted the press for a few days had it not been for a mishap that was more a publicity triumph than a catastrophe. Late one rainy night the car dropped into an enormous hole filled with water. The trio called into the darkness for help until they were hoarse, but their cries were met only with the splatter of rain on surrounding wheat. Sara – thinking she had seen a farmhouse a mile or two back – climbed out of the car with characteristic resolution, to pit her ninety pounds against the mud and driving rain. “It seemed to me it was ten miles,” she recalls. “I didn’t have boots; the mud began to get up to my knees, and I would have to keep moving over, criss-crosswise, to places where I could see a footing.”

After a lifetime of slogging through the ooze, Sara found the farmhouse and a sleepy farmer – understandably astonished to find in his doorway this large lump of black mud, with little more than an embarrassed smile showing through. He brought out two large work horses and a truck, and drove her back. Sara remembers that he didn’t quite grasp the significance of her suffrage lecture, but he did concede, “Well , you girls got guts.”

After the farmer extracted them from the mud hole, the “girls” continued to Kansas City. Their bags had gone on by train, and the intrepid Sara was temporarily grounded in the Emporia hotel while her mud-caked suit – her only traveling suit was at the cleaners. Meanwhile, the equally intrepid editor of the Emporia Gazette, William Allen White, came upstairs for an interview. “I had to see him in bed,” Sara remembers. “with I hope the proper covering. He was both highly amused and extremely awed by the whole project. We had a delicious interview. He left and said, ‘This is very French.’”

White gave his humor free reign in the column. “They got on a famously,” he wrote, “until they struck Nickerson and stuck in the mud . . . and having no man along to do the swearing, it was sheer strength and moral courage that got them through. But they had to wade in the mud up to their hose-supporters.” In a gesture of Kansas gallantry, White did not print the very French circumstances of the interview.

Clean and refreshed, the trio was heading toward Missouri when it learned the results of the suffrage election in New Jersey. This was the state where President Wilson had publicly announced his support of suffrage (as long as it was won state by state) and cast his own “yes” vote, but even this impressive support was not enough. Suffrage was voted down – reinforcing the Congressional Union in its conviction that efforts should concentrate on the passage of a national amendment.

The smiling crowds and enthusiastic support of officials in Kansas City, Kansas, contrasted sharply with the cold reception of Senator James A. Reed across the river in Missouri – the first “enemy” country. Even though Mabel Vernon had arranged a procession of the “most prominent women,” Reed put aside their eloquent pleas by answering only that he would “take the matter into consideration.” However, Sara reported that at the street meetings they had more people to talk to than their voices could reach, and that the older suffrage workers saw new hope with the power of the enfranchised western women being used in Congress on their behalf. “The greatest day for suffrage Kansas City has ever seen,” glowed one. The car rattled on toward Topeka, Lincoln, and Chicago.

The smiling crowds and enthusiastic support of officials in Kansas City, Kansas, contrasted sharply with the cold reception of Senator James A. Reed across the river in Missouri – the first “enemy” country. Even though Mabel Vernon had arranged a procession of the “most prominent women,” Reed put aside their eloquent pleas by answering only that he would “take the matter into consideration.” However, Sara reported that at the street meetings they had more people to talk to than their voices could reach, and that the older suffrage workers saw new hope with the power of the enfranchised western women being used in Congress on their behalf. “The greatest day for suffrage Kansas City has ever seen,” glowed one. The car rattled on toward Topeka, Lincoln, and Chicago.

Topeka was the only place on the entire trip that Sara actually missed a meeting. Mabel Vernon had the press, a band, and autos organized for the arrival; in their enthusiasm, the women of that city had procured letters of suffrage endorsements from every official they could contact, from the attorney general to the state printer. The crowd gathered, but there was no trace of car or envoy – Sara and her companions were sitting sixty miles away with the vague infliction of “tire trouble and engine difficulties.” For two hours Mabel held the crowd until all gave up and went home. The added publicity of the trio’s Kansas disasters, however, only added to the crusade’s impact. When the car finally pulled into Topeka, Sara found that even the Kansas governor had been moved to send a letter of support.

As the car bounced through gala receptions and parades in Lincoln, Nebraska, and Des Moines and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, a further calamity developed that might have sent less dedicated campaigners home to the kitchen for good. Perhaps it was after a particularly triumphant reception- Sara cannot remember exactly the time and place – when Miss Kindstedt turned to her, accused her of grabbing the limelight and announced: “At the end of this trip I’m going to kill you!”

Although Miss Kindborg, the driver, tried to keep Sara from worrying about the threat, continuing growls and glares from the mechanician’s seat left Sara with little peace of mind, especially during the lonely stretches between stops.

About the same time, news arrived of three more suffrage elections and three more defeats: New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts, all of which lay ahead to challenge Mabel’s energies and Sara’s magic words.

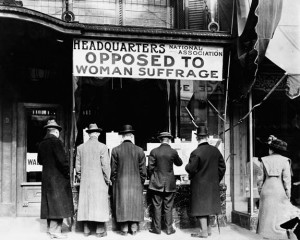

But first, Illinois (where women had recently won the right to vote for national offices only) and a boisterous welcome on Chicago’s famed Michigan Avenue. Streets were blocked off, and Sara spoke to a “sea of people” from the steps of the Art Institute; Mayor Big Bill Thompson bestowed his ample blessings on the whole campaign, and a large chorus sang out with Sara’s own “Hymn of Free Women.” Here too, came the first serious heckling by anti-suffrage people. “The women were the worst,” Sara recalls. “the right-wing D.A.R. and all associations of that kind were extremely ‘anti’, and they sent their speakers right on my trail in the East.” There was also a widespread belief that, once women got the vote, prohibition would surely follow; consequently the opposition had powerful political financial support from the liquor lobby. The crescendo of parades, speeches, and new Union chapters nevertheless increased in Indianapolis and Columbus. Detroit – perhaps because it had been Sara’s home town – was the biggest success ever. Four thousand signatures lengthened the petition there, and night skies exploded with fireworks.

But first, Illinois (where women had recently won the right to vote for national offices only) and a boisterous welcome on Chicago’s famed Michigan Avenue. Streets were blocked off, and Sara spoke to a “sea of people” from the steps of the Art Institute; Mayor Big Bill Thompson bestowed his ample blessings on the whole campaign, and a large chorus sang out with Sara’s own “Hymn of Free Women.” Here too, came the first serious heckling by anti-suffrage people. “The women were the worst,” Sara recalls. “the right-wing D.A.R. and all associations of that kind were extremely ‘anti’, and they sent their speakers right on my trail in the East.” There was also a widespread belief that, once women got the vote, prohibition would surely follow; consequently the opposition had powerful political financial support from the liquor lobby. The crescendo of parades, speeches, and new Union chapters nevertheless increased in Indianapolis and Columbus. Detroit – perhaps because it had been Sara’s home town – was the biggest success ever. Four thousand signatures lengthened the petition there, and night skies exploded with fireworks.

Winter had come to the East, and in Cleveland, Sara spoke in the public square in a swirling snow storm, extracting from Congressman Emerson a promise to vote for the amendment. In Buffalo the mayor and many others signed. Just before Syracuse another disaster befell the car – a broken axle. The local garage had no Overland axles in stock and the situation looked bleak. But dauntless Sara wired Toledo for a new part, and they all made the Syracuse reception on time. Utica followed; then Albany, where a meeting in the executive mansion itself – a courageous gesture for the governor of a state that had just voted down woman suffrage – broke all precedent. The governor looked down at Sara and said, “I thought you would be ten feet tall.”

Ironically, Sara was feeling neither tall nor robust. Her vigor was beginning to wane from so many weeks of public appearances, tense travels with Miss Kindstedt, and the incessant bouncing of the cumbersome Overland, which had pounded her black and blue. Frances Jolliffe arrived in Albany by train to rejoin Sara as a much needed fellow speaker for the high-pressure days ahead. As they set out for Boston, Alice Paul, down in Washington, was whipping eastern amendment-minded suffragists into viable organizations. The opposition held Boston as its bastion, but the fervor of the recently defeated suffragist was intense. Great throngs gathered about the three speakers. In the rotunda of the Captiol, Governor Walsh offered his letter of personal endorsement of the amendment, but during Sara’s ringing speech he whispered to Mabel Vernon, “ don’t ask me to sign the petition, don’t ask me to sign!”

All during the trek eastward Sara had kept a worried vigil on the volatile Miss Kindstedt, so at the Swede’s American home of Providence, Rhode Island, the two car owners were left for a rest. Sara and Frances took the train to New York, and the battered little car was shipped down by boat. Covered with dents and plastered with stickers from cities all across the continent, it drove off the dock to Fifth Avenue to join the biggest parade of them all. “Fifth Avenue rubbed its eyes,” the New York Sun reported, “when the weather-beaten automobile, bearing the slogan ‘On to Congress!’ and followed by a hundred other cars, blazed a path of purple and gold down the great thoroughfare.” The management of Sherry’s lent its great ballroom for a meeting, which overflowed before the speaking began.

Frances Jolliffe, “a tired little woman in a travel-worn brown suit,” as the New York Tribune described her, “stood in the glitter of a Sherry’s ballroom and held out a tired little brown hand. ‘We, the voting women of the West, want to help you,’ she pleaded. ‘Will you let us?’ The audience was moved to tears and action …” raising six thousand dollars.

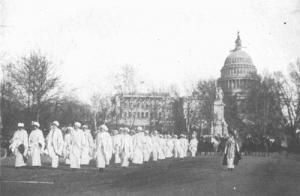

Leaving New York, the envoys headed for Washington, D.C., and the climax of their trip, Sara overcame her increasing fatigue and endured parades and speeches in Newark, Philadephia, Wilmington, and Baltimore. Finally, in December, the day before Congress convened, the car, banner in place, moved slowly down the Baltimore turnpike and stopped at the edge of Washington. Novelist Mary Austin took charge of assembling the grand procession: women tall on horseback, each representing a suffrage state; flag – and banner-bearers wearing long purple capes and gold collars with flowing white stoles; a replica of the Liberty Bell, “lavishly decorated”; hundreds of other women carrying purple, white , and gold pennants: three hundred “distinguished” guests heading the procession; and , of course, the great petition, unrolled only to a hundred of its eighteen thousand feet, carried by special bearers. The battered little car took its place in the lead, with Sara, Frances Jolliffe, Mabel Vernon, and the two Swedes, inside. Flowing through the streets of Washington as a brilliant river of color, the parade finally arrived at the steps of the nations’ Capitol, where a large delegation of congressmen awaited Sara at the top of the white marble steps. Slowly, she mounted the steps and Frances Jolliffe, the long petition borne majestically behind them as a symbol of western power. The envoys exchanged speeches with two carefully selected lawmakers. Senator David Sutherland and Representative Stephan Mondell. Said Sutherland, “… backed as it is by four million voting women, the suffrage amendment should receive the most serious attention of Congress.”

Leaving New York, the envoys headed for Washington, D.C., and the climax of their trip, Sara overcame her increasing fatigue and endured parades and speeches in Newark, Philadephia, Wilmington, and Baltimore. Finally, in December, the day before Congress convened, the car, banner in place, moved slowly down the Baltimore turnpike and stopped at the edge of Washington. Novelist Mary Austin took charge of assembling the grand procession: women tall on horseback, each representing a suffrage state; flag – and banner-bearers wearing long purple capes and gold collars with flowing white stoles; a replica of the Liberty Bell, “lavishly decorated”; hundreds of other women carrying purple, white , and gold pennants: three hundred “distinguished” guests heading the procession; and , of course, the great petition, unrolled only to a hundred of its eighteen thousand feet, carried by special bearers. The battered little car took its place in the lead, with Sara, Frances Jolliffe, Mabel Vernon, and the two Swedes, inside. Flowing through the streets of Washington as a brilliant river of color, the parade finally arrived at the steps of the nations’ Capitol, where a large delegation of congressmen awaited Sara at the top of the white marble steps. Slowly, she mounted the steps and Frances Jolliffe, the long petition borne majestically behind them as a symbol of western power. The envoys exchanged speeches with two carefully selected lawmakers. Senator David Sutherland and Representative Stephan Mondell. Said Sutherland, “… backed as it is by four million voting women, the suffrage amendment should receive the most serious attention of Congress.”

With one eye on the gathering clouds of Wold War I, Congressman Mondell added, “We trust that the pressure of other matters of importance will not be made an excuse for delaying or postponing action on this highly important question… Under free government there can be no more important question than one involveing the suffrage right sof half the people.” The procession from the Capitol to the white House attracted more spectators, in spite of a very cold day. Rolling to a halt in the semi-circular drive of the White House, Sara, her convoy, and the three hundred distinguished guests were escorted to the East Room, where President Wilson awaited them.

Ida Husted Harper was to describe the event in a speech the following evening: “ To my mind the most impressive and historic scene was that of three little women voters from three of the states of the far West pleading for the political liberty of their millions of disfranchised sisters. How I wish that picture could be immortalized on canvas – those three young faces, gazing so eagerly and hopefully into the serious and interested countenance of the President, as he stood there and listened.”

Sara was saying, “And Mr. President, as I am not to have the woman’s privilege of the last word, may I say that I know what your stand has been in the past, that you have said it was a matter for the states to decide. But we have seen that, like all great men, you have changed your mind on other questions. We have watched the change and development of your mind on preparedness, and we honestly believe that circumstances have so altered that you may change your mind in this regard.”

Sara was saying, “And Mr. President, as I am not to have the woman’s privilege of the last word, may I say that I know what your stand has been in the past, that you have said it was a matter for the states to decide. But we have seen that, like all great men, you have changed your mind on other questions. We have watched the change and development of your mind on preparedness, and we honestly believe that circumstances have so altered that you may change your mind in this regard.”

They asked that he glance at the petition. Four miles of signatures unrolled and hit the opposite wall of the ornate room. As he looked, perhaps astonished, Sara reminded him gently that many of the signatures were those of the governors, mayors, and congressmen of the cities through which they had passed. With the help of two of the women, the president rolled the petition up, then said, “I did not come here anticipating the necessity of making an address of any kind. As you have just heard,” And he smiled in Sara’s direction, “I hope it is true that I am not a man set stiffly beyond the possibility of learning . . . Nothing could be more impressive than the presentation of such a request in such numbers and backed by such influences as undoubtedly stand behind you… However, I do not like to speak for others until I consul them and see what I am justified in saying.

“this visit of yours will remain in my mind not only as delightful compliment, but also as a very impressive thing, which undoubtedly will make it necessary for all of us to consider very carefully what is right for us to do.”

Today Sara says, “I remember that I could see at once that he would be a hard man to convince of anything that he did not spontaneously believe. But he listened to what you were saying. And his face: you could tell by his eyes that he was following what you said.

“Oh, the women went out jubilant. They thought this was the turning point. They thought he was going to back the amendment in Congress.”

The President did back the amendment, but not in that congress. It came three years later, and the day after his statement of support, it passed the heretofore unyielding House of Representatives with but one vote to spare. And it was not until spring of 1919 that it finally cleared both houses in the same session. Tennessee, the last state needed in the tedious ratification that followed, capitulated on August 18 of the following year – just in time for the new voters to exercise the power of their ballot in the 1920 election.

It had cost the human effort of a small war: imprisonments, illnesses, and in a few cases, deaths. But the revitalization might never have come to the stagnant cause of suffrage without the youth and vigor of those who, in the brilliance of the San Francisco fair, united the enfranchised women of the West and sent their power eastward.

(Sara Bard Field – A western poet and libertarian,l she carried the message of freedom to the voteless women of the East in an age when transcontinental automobile travel was an adventure not far removed from the travails of the wagon-train days.)

The great palace was softly and naturally lit except for the giant tower gate flaming aloft in the white light, focused on it as on some brilliant altar. Far below, like a brilliant flower bed, filling the terraced stage from end-to-end, glowed the huge chorus of women…

And then came the envoys, delegated by women voters to carry the torch of liberty through the dark lands and keep it burning. And the dark mass below the lighted altar-tower caught the crusader’s spirit and burst into cheers… Orange lanterns swayed in the breeze; purple, white and gold draperies fluttered, the blare of the band burst forth, and the great surging crowd followed the envoys to the gates…

To the wild cheering of the crowd, Miss Jolliffe and Mrs. Field were seated. The crowd surged close with final messages. Cheers burst forth as the gates opened and the big car swung through, ending the most dramatic and significant suffrage convention that has probably ever been held in the history of the world.

Related Books Go HERE!

activist Alice Paul America campaign Congress equal rights Freedom President Wilson Rights Suffrage women