Hope! The Simpleton and Common sense.

The following article, written over a half century ago, I recently stumbled across and for myself it was one that I could not let go of. I read and re-read several times, each leaving me with new visions of what was and what is, of what I hope to be and what I hope I am. I researched, found, and got permission to post this article here to share with you. I hope that you will take the time to read in it’s entirety and your thoughts good or bad will enjoy it as much as I and share with others.

The Geography of Hope:

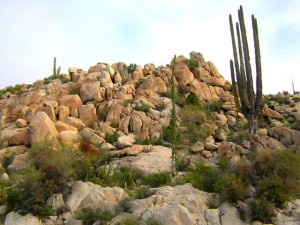

“It is a lovely and terrible wilderness, such a wilderness as Christ and the prophets went out into; harshly and beautifully colored, broken and worn until its bones are exposed, its great sky without a smudge or taint from the Technocracy…. Save a piece of country like that intact, and it does not matter in the slightest that only a few people every year will go into it. That is precisely its value…. We simply need that wild country available to us, even if we never do more than drive to its edge and look in. For it can be a means of reassuring ourselves of our sanity as creatures, a part of the geography of hope”:

“It is a lovely and terrible wilderness, such a wilderness as Christ and the prophets went out into; harshly and beautifully colored, broken and worn until its bones are exposed, its great sky without a smudge or taint from the Technocracy…. Save a piece of country like that intact, and it does not matter in the slightest that only a few people every year will go into it. That is precisely its value…. We simply need that wild country available to us, even if we never do more than drive to its edge and look in. For it can be a means of reassuring ourselves of our sanity as creatures, a part of the geography of hope”:

The geography of hope, as Wallace Stegner has described it, is a rapidly diminishing resource on the American continent in an age in which hope itself becomes increasingly scarce. In one of its most recent “Exhibit Format” publications, the Sierra Club of California has produced a stunning memorial to one of the few lands left whose harshness, isolation, and beauty remains biblical amid the clutter of the twentieth century; the long peninsula of Baja California. With a pungent, reflective text compiled from the works of naturalist-philosopher Joseph Wood Krutch, and the artistry of Eliot Porter’s camera, Baja California and the Geography of Hope is a monument to a land not yet altered to man’s purposes.

The discovery of America meant different things to different people. To some it meant only gold and the possibility of other plunder. To others less mean-spirited it meant a wilderness which might in time become another Europe. But there were also not a few whose imaginations were most profoundly stirred by what it was rather than by what it might become.

The discovery of America meant different things to different people. To some it meant only gold and the possibility of other plunder. To others less mean-spirited it meant a wilderness which might in time become another Europe. But there were also not a few whose imaginations were most profoundly stirred by what it was rather than by what it might become.

The wilderness and the idea of the wilderness is one of the permanent homes of the human spirit. Here, as many realized, had been miraculously preserved until the time when civilization could appreciate it, the richness and variety of a natural world which had disappeared unnoticed and little by little from Europe. America was a dream of something long past which had suddenly become a reality. It was what Thoreau called the great “poem” before many of its fairest pages had been ripped out and thrown away. The desire to experience that reality rather than to destroy it drew to our shores some the best who have ever come to them.

Albert Einstein once told the students at the California Institute of Technology that he doubted whether present-day Americans were any happier than the Indians who were inhabiting the continent when the white man first came. Not many are likely to agree with so extreme a statement but quite a few, I think, would admit that, leaving the Indians out of it, we are not as much happier than our grand-fathers as it would seem out gains in health, security, comfort, convenience, as well as our release from physical pain out to make us. Does this failure to pay off have something to do with a misjudgment concerning what man really wants most or, at least, a failure to take into account certain of the things he wants besides comfort, wealth and the rest?

Albert Einstein once told the students at the California Institute of Technology that he doubted whether present-day Americans were any happier than the Indians who were inhabiting the continent when the white man first came. Not many are likely to agree with so extreme a statement but quite a few, I think, would admit that, leaving the Indians out of it, we are not as much happier than our grand-fathers as it would seem out gains in health, security, comfort, convenience, as well as our release from physical pain out to make us. Does this failure to pay off have something to do with a misjudgment concerning what man really wants most or, at least, a failure to take into account certain of the things he wants besides comfort, wealth and the rest?

By 1980, they say, you will be broiling steaks in electronic stoves, owning a two-helicopter garage and, of course looking at television in full color. These assurances are supposed to make it easier for the housewife to put up with mere electric ovens, ninety-mile-an-hour automobiles and soap operas in black and white. From such makeshifts they are supposed to lift sparkling eyes toward a happier future. And perhaps that is precisely what they do do. But will they be as much happier as they now think they inevitably must be? Is it really what they want? Is the lack of these things soon to come chiefly responsible for the irritations, frustrations and discontents they now feel?

Suppose they were promised instead that by 1980 the world in which they live will be less crowded, less noisy, less hurried and, even, less complicated. Suppose they were told that they will have more opportunities to see the beauties and to taste the pleasures of sea and mountain and stream, to have more contact with the wonders of trees and flowers, the abounding life of animal creatures othern than human. Would the prospect look even brighter?

Suppose they were promised instead that by 1980 the world in which they live will be less crowded, less noisy, less hurried and, even, less complicated. Suppose they were told that they will have more opportunities to see the beauties and to taste the pleasures of sea and mountain and stream, to have more contact with the wonders of trees and flowers, the abounding life of animal creatures othern than human. Would the prospect look even brighter?

What philosophers used to call “the good life” is difficult to define and impossible to measure. In the United States today- increasingly also in all “progressive” countries- we substitute for it “the standard of living,” which is easy to measure if defined only in terms of wealth, health, comfort, and convenience. But the standard of living does not truly represent the goodness of a life unless you assume that no other goods are real.

No one could call either the few scattered inhabitants of Baja’s open country or those who inhabit La Paz, its southern metropolis, “affluent”. Here is an economy, not of abundance, but of desperate scarcity, where food and water are hard to come by and manufactured goods so scarce that “use up and make do” are not a philosophy but an inescapable necessity, and most things that cannot serve their original purpose any longer are made to serve some other. No one there is likely to be able to understand what is meant by the necessity for an advertising art to “create needs” or by the dangers of “underconsumption.”

That one meets there smiling children and seemingly contented men may seem to prove that theirs is to some degree a good life. “Swept and garnished: is the phrase which sums up, not only La Paz, but all except the most forlorn of the villages. Though chickens may wander around palm-thatched huts there is no dismal accumulation of trash like that which disgraces almost every American community. In La Paz the buildings may be in need of repair but they are not frowzy- only resigned, so it seems, to the inevitable decline which a clean old man accepts….

With us, advertisers solemnly congratulate themselves upon their success in “creating needs”; there, even minimal needs are hard to satisfy. There, to revert again to abstraction, is an economy of almost unqualified scarcity; here, one of almost unqualified abundance….

Because of that start fact, men not only live differently and act differently; they also think and feel differently. Here we seek excuses to discard, replace, and throw away. We are a little ashamed to use up or wear out; indeed we are sometimes told that to do so is to threaten with disloyalty the very prosperity which makes it possible to have more than we need. But it will be a long time before the inhabitants of Baja are able to grasp even as an abstraction the concept of “psychological obsolescence.” “Use it up” and “make do” are more than merely necessary habits; they are moral injunctions.

When some physical object can no longer serve the purpose for which it was first intened there is nearly always something else for which it can be used. The automobile which has been repaired until it can be repaired no more supplies spare parts for another one not quite so far gone and, indeed, may serve with gradually reduced efficiency in our vehicles after another. Thus, “made” things return to the earth by a series of stages somewhat like those by which the body of a man, once the most complex of machines, is reduced step by step to simple inorganic chemicals, his protoplasm feeding first, perhaps, some lower animal, then some vegetable growth, then the bacteria of decay, and thus becomes successively protein, an amino acid and, at long last, merely carbon, calcium, and phosphorus again. Similarly machines, tools, and even bottles and boxes disintegrate in Baja as they serve simpler and simpler uses. The hood of a no longer usable car becomes the roof of the lean-to or part of one side of a shack; the empty soup can grows an ornamental plant; the bottom of a broken bottle outlines a flower bed; the discarded tire serves as the sole of a sandal and has become, I believe, an article of commerce.

When some physical object can no longer serve the purpose for which it was first intened there is nearly always something else for which it can be used. The automobile which has been repaired until it can be repaired no more supplies spare parts for another one not quite so far gone and, indeed, may serve with gradually reduced efficiency in our vehicles after another. Thus, “made” things return to the earth by a series of stages somewhat like those by which the body of a man, once the most complex of machines, is reduced step by step to simple inorganic chemicals, his protoplasm feeding first, perhaps, some lower animal, then some vegetable growth, then the bacteria of decay, and thus becomes successively protein, an amino acid and, at long last, merely carbon, calcium, and phosphorus again. Similarly machines, tools, and even bottles and boxes disintegrate in Baja as they serve simpler and simpler uses. The hood of a no longer usable car becomes the roof of the lean-to or part of one side of a shack; the empty soup can grows an ornamental plant; the bottom of a broken bottle outlines a flower bed; the discarded tire serves as the sole of a sandal and has become, I believe, an article of commerce.

A century ago the naturalist, Xantus, complained that he could find no boxes in which to ship his specimens because the few which turned up in Baja were quickly seized and made into furniture. Times have not changed as much as one might expect. In the wilds near a small village I saw boys digging up the camp trash we had buried in order to salvage tine cans. In La Paz itself the humbler housewives carefully avoid crushing the shells of the eggs they eat in order that these shells may be sold for an infinitesimal fraction of a cent to merchants who stuff them with confetti and then sell them again to the revelers at Mardi Gras who delight to break them finally over one another’s heads.

Up to the present, mankind may have profited more than it has suffered from the various powers it has been able to exercise. Let us assume that it has. But that is, at best, no more than good luck. At no moment has it ever known or, indeed, seriously considered what the consequences were likely to be. What actually happens when the steam engine or the dynamo or, for that matter, the automobile, the airplane, and the radio, is invented is simply this; Our hearts lift up and we let out a glad cry, “Hold on t your hats boys, here we go again.”

Up to the present, mankind may have profited more than it has suffered from the various powers it has been able to exercise. Let us assume that it has. But that is, at best, no more than good luck. At no moment has it ever known or, indeed, seriously considered what the consequences were likely to be. What actually happens when the steam engine or the dynamo or, for that matter, the automobile, the airplane, and the radio, is invented is simply this; Our hearts lift up and we let out a glad cry, “Hold on t your hats boys, here we go again.”

Even if it is assumed that more good than evil has always resulted so far, the results have certainly not all been unqualifiedly good. There was a time when the whole question of the industrial revolution hung in the balance. For a generation it enslaved children and they were freed just in the nick of time – 1.e., just before child slavery could become an accepted social institution. At the present moment millions of children instead of standing in front of looms are seated in a seemingly milder enslavement before “giant twenty-one inch screens,” hypnotized by a distant and usually anonymous masters who find it profitable in one way or another when certain images, sounds, and reiterated statements are presented to the eyes and ears of their victims.

It was nothing like this which Marconi, De Forest and the rest intended. Neither was it the enslavement of children nor the creation of poisonous smog clouds that Watt intended. But all these things were among the direct consequences. Who know how this generation of children is to be set free?

In the Sanskrit Panchatantra, that collection of romantic tales written down in an early century A.D. there is a fable which might have been devised for today. Three great magicians who have been friends since boyhood have continued to admit to their fellowship a simple fellow who was also a companion of their youth. When the three set out on a journey to demonstrate to a wider world the greatness of their art they reluctantly permit their humble friend to accompany them, and before they have gone very far, they come upon a pile of bones under a tree. Upon this opportunity to practice their art they eagerly seize. “I,” says the first,” can cause these dead bones to reassemble themselves into a skeleton.” And at his command they do so. “I”, says the second, “can clothe that skeleton with flesh.” And his miracle, also, is performed. Then, “I,” says the third, “can now endow the whole with life.”

In the Sanskrit Panchatantra, that collection of romantic tales written down in an early century A.D. there is a fable which might have been devised for today. Three great magicians who have been friends since boyhood have continued to admit to their fellowship a simple fellow who was also a companion of their youth. When the three set out on a journey to demonstrate to a wider world the greatness of their art they reluctantly permit their humble friend to accompany them, and before they have gone very far, they come upon a pile of bones under a tree. Upon this opportunity to practice their art they eagerly seize. “I,” says the first,” can cause these dead bones to reassemble themselves into a skeleton.” And at his command they do so. “I”, says the second, “can clothe that skeleton with flesh.” And his miracle, also, is performed. Then, “I,” says the third, “can now endow the whole with life.”

At this moment the simpleton interposes. “Don’t you realize,” he asks, “that this is a tiger?” But the wise men are scornful. Their science is “pure”; it has no concern with such vulgar facts. “Well then,” says the simpleton, “wait a moment.” And he climbs a tree. A few moments later the tiger is indeed brought to life. He devours the three wise men and departs. Thereupon the simpleton comes down from his tree and goes home.

There is no more perfect parable to illustrate what happens when know-how becomes more important than common sense- and common sense is at least the beginning of wisdom.

I hope you will share with others: social media button below.

Source: Originally published Jan. 1968 The American West

Author: Joseph Wood Krutch

America Baja California Common sense Hope Joseph Wood Krutch The Geography of Hope wilderness